In the 17th century an extensive intellectual, diplomatic, religious and political network extended its influences from the Irish College into universities, religious orders, the courts of France, Spain and the Papacy. Actions initiated in the Irish College were felt not only in Ireland but in England and across Europe.

History of the Irish College in Leuven

The Foundation of the College

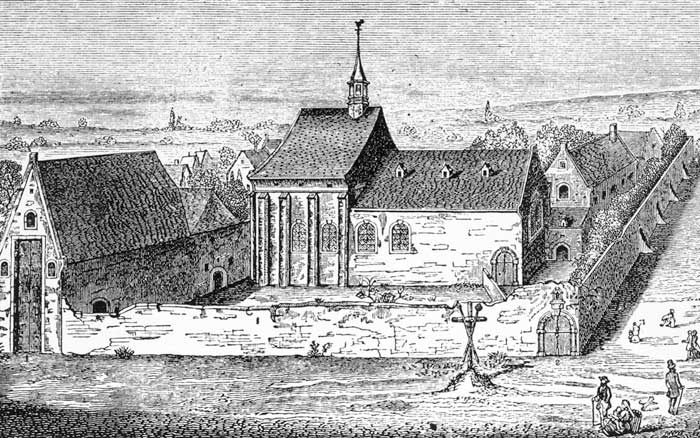

In the early 1980’s the Irish Franciscans generously made the historic Irish College in Leuven available to the Leuven Institute for Ireland in Europe ivzw for development as a resource for the people of Ireland. The Irish College in Leuven was founded in 1607 by the Irish Franciscan, Florence Conry, who was himself the product of an Irish College, having studied in Salmanca. The Archdukes Albert and Isabella, co-rulers of the Spanish Netherlands, took a keen interest in the fortunes of the college and personally attended the ceremony to lay the foundation stone of the building in 1617.

The role of the Irish College as a focal point of Irish and European affairs was already demonstrated in the winter of 1607 when Florence Conry brought Hugh O’Neill and his retinue to Leuven following their departure from Ireland in what became known as the Flight of the Earls.

The Spanish Connection

At the time the Irish College was founded, Ireland was caught between Spanish and English influences and became the object of a tug of war between Catholic and Protestant Europe. Leuven was part of the Spanish Netherlands which was ruled by the Archduke Albert and his wife Isabella, half-sister of King Philip III of Spain.

At the time the Irish College was founded, Ireland was caught between Spanish and English influences and became the object of a tug of war between Catholic and Protestant Europe. Leuven was part of the Spanish Netherlands which was ruled by the Archduke Albert and his wife Isabella, half-sister of King Philip III of Spain.

Philip, Albert, and Isabella, took a close interest in the founding of the Irish College. In a letter of 1606 to Albert Phillip referred to Friar Florence Conry’s petition to found a college in Leuven because of the difficulties in educating Catholic scholars in Ireland. (This letter can be explored in detail in the interactive near the foundation stone). The King approved the project and granted the College 1000 ducats per year.

Another letter written by Archduke Albert and dated May 1607, introduced Florence Conry to the university, explained the active support of the king and asked the university authorities to give every possible support to this newly founded Irish College.

The early work of the Leuven friars was especially relevant to those Irish who lived in Spanish realms. By evoking the legend of the Milesians, which held that the ancestors of the Irish people had come from Spain, they were able to demonstrate truly ancient links between the Iberian Peninsula and the Island of Ireland. This was a very useful device for the integration of exiled Gaelic nobles and professionals into the ancestry-driven Spanish social system. As testament to the Irish-Spanish link, after his death in Madrid in 1629 Florence Conry was accorded a royal funeral. In 1654 his remains were translated to the Irish College, Leuven.

The Grand Project

At the start of the 17th Century Ireland was little known and little understood in Europe. Irish Exiles and migrants such as the friars wanted to overturn stereotypes about their country, past and present to European audiences. They wished to place the Irish as one of the most ancient peoples in Europe and linked to this was a desire to overcome longstanding accusations of barbarity against the Irish. They also had to overcome confusion between Scotland and Ireland, compounded by early Latin writers who had referred to Ireland as “Scotia” and the Irish as “Scoti”. In the decades after the foundation of the Irish College, Leuven, the Franciscans dedicated themselves to providing an intellectual underpinning for this kind of Irishness. They aimed to bring Ireland “into” Europe, but in doing so engaged with the language and the great bulk of medieval learning in such a way that the memory of the Gaelic world was itself recast as a European idiom.

At the start of the 17th Century Ireland was little known and little understood in Europe. Irish Exiles and migrants such as the friars wanted to overturn stereotypes about their country, past and present to European audiences. They wished to place the Irish as one of the most ancient peoples in Europe and linked to this was a desire to overcome longstanding accusations of barbarity against the Irish. They also had to overcome confusion between Scotland and Ireland, compounded by early Latin writers who had referred to Ireland as “Scotia” and the Irish as “Scoti”. In the decades after the foundation of the Irish College, Leuven, the Franciscans dedicated themselves to providing an intellectual underpinning for this kind of Irishness. They aimed to bring Ireland “into” Europe, but in doing so engaged with the language and the great bulk of medieval learning in such a way that the memory of the Gaelic world was itself recast as a European idiom.

As they embarked on this ambitious project, the Friars drew the attention of the English authorities. In 1615, the English agent in Brussels, William Turnbull, described the Irish Franciscan community in Leuven as “perfidious Machiavellian friars”. His uncomplimentary comments were ironic given that Conry, along with many of the friars, recognised the legitimacy of the Stewart Kings as rulers of Ireland. Turnbull deplored the Franciscans’ attempts to replace the old medieval divisions between Anglo-Norman and Gaelic Irish with a new Irish identity.

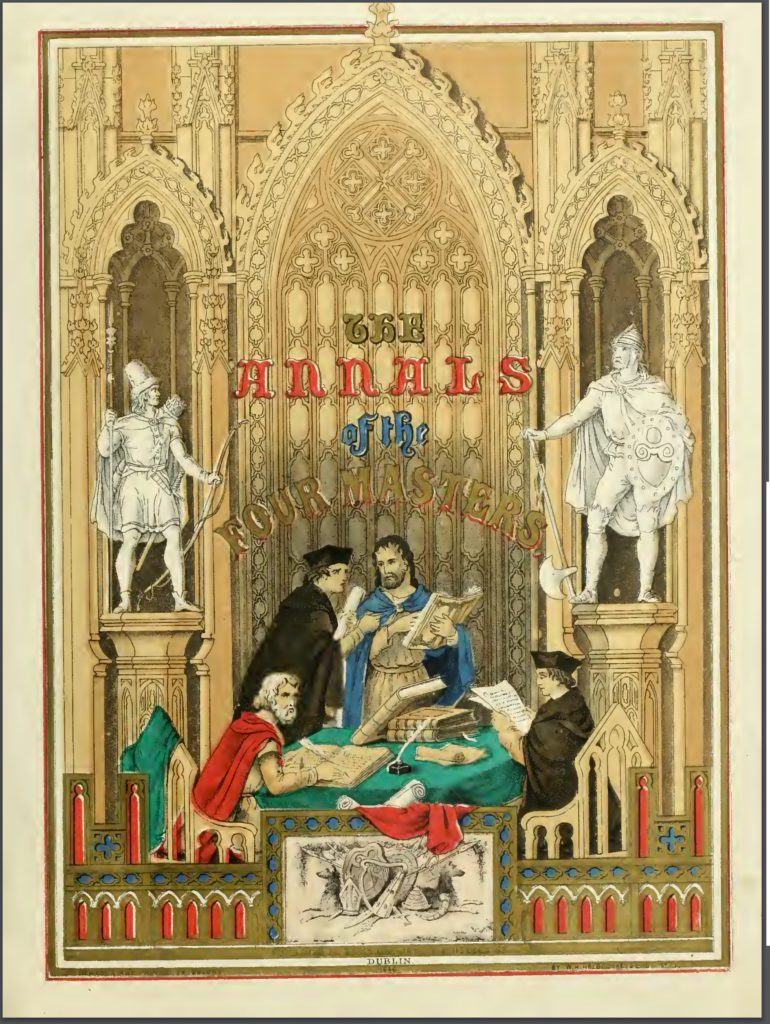

Nonetheless this vast undertaking, known as “the Grand Project”, prospered. It ranged from the production of simple cathechisms to its most famous expression in the Annals of the Four Masters. The Annals bear eloquent witness to the vigorous cross-fertilisation of Irish and European influences that working in Leuven made possible. The “Grand-Project” had four main pillars – the Irish language, collecting and preserving Irish history, vindicating Ireland’s ancient sanctity, and demonstrating Ireland’s tradition of scholarship. The success of the work laid the foundation of a new Irish cultural identity.

Hugh Mc Caughwell (Aodh McAingil) 1571 -1626

Hugh Mc Caughwell, Guardian of the Irish College in Leuven, was educated on the Isle of Man and at Salamanca. He was an exceptional scholar of languages, law, philosophy and theology and took particular interest in interpreting the works of the medieval philosopher and theologian John Duns Scotus. McCaughwell’s enthusiasm for Duns Scotus was partly prompted by English and Polish denials of Scotus’ Irishness and in 1620 he wrote a spirited defence of his hero’s Downpatrick roots.

Hugh Mc Caughwell, Guardian of the Irish College in Leuven, was educated on the Isle of Man and at Salamanca. He was an exceptional scholar of languages, law, philosophy and theology and took particular interest in interpreting the works of the medieval philosopher and theologian John Duns Scotus. McCaughwell’s enthusiasm for Duns Scotus was partly prompted by English and Polish denials of Scotus’ Irishness and in 1620 he wrote a spirited defence of his hero’s Downpatrick roots.

Although the theological issues with which McCaughwell and his colleagues Conry and Wadding were engaged may look obscure and dry form a distance, they brought Irish scholarship in Latin to the very front of the European stage in an era when kings and princes deemed theologians as necessary to their government as they did diplomats. McCaughwell, like so many of these 17th century friars, was also very accomplished in his native tongue. His poem Dia do Bheatha is still sung as a Christmas carol.

McCaughwell was closely associated with Hugh O’Neill and was at one time tutor his sons. He acted as an intermediary between the English court and O’Neill after the Flight of the Earls in the hope that O’Neill could return to Ireland. These negotiations failed but throughout his career in Spain, Leuven and finally in Rome, McCaughwell continued to petition for aid to be sent to Ireland. He was appointed Archbishop of Armagh but died in Rome in 1626 before he could return home to take up a post.

John Colgan c. 1592 – 1643

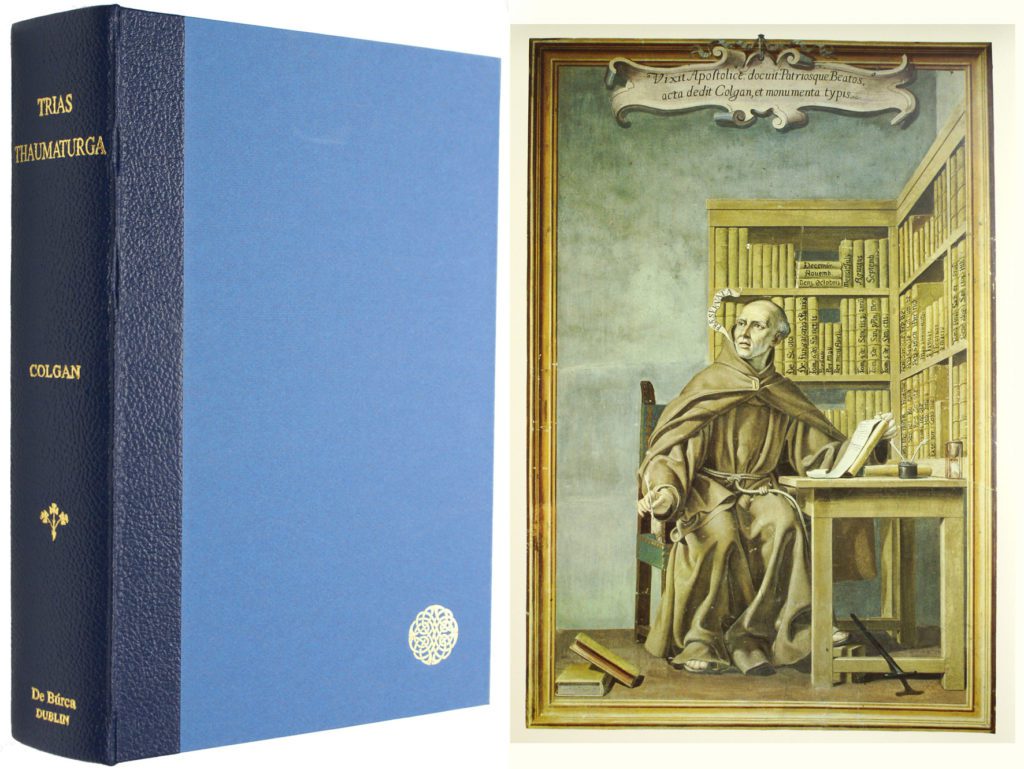

John Colgan was born in Donegal but spent much of his life in continental Europe. Colgan joined the community in the Irish College, Leuven in 1620 and took over the work of vindicating Ireland’s ancient sanctity begun by Hugh Ward, Hugh McCaughwell, Thomas Messingham and other Irish scholars.

In 1645 Colgan published Acta Sanctorum ….Hiberniae Sanctorum Insulae which contained all the Irish saints whose feast-days fell in January, February and March. Two years later he published Triadis Thaumaturgae, a vast compendium of everything known about the three patrons of Ireland, Patrick, Brigid and Columba.

This work lifted Ireland’s saints into international view, thus legitimising them and in so doing, proving that the true Irish church was the Roman Catholic Church. It was also part of a wider Counter Reformation effort, led by the Jesuits, to document the lives of all the European Saints.

Colgan and other Leuven Franciscans were very frank about their purpose, repeatedly stating that it was for “the honour of Ireland”. Colgan’s work on Patrick paved the way for Irish Franciscan Luke Wadding’s successful campaign to have St. Patrick’s Day designated as a feast in the universal Roman calendar. In Leuven the Irish community promoted Patrick by procuring indulgences for observation of the feast-day and by instituting a public sermon and other festivities.

It was Colgan who, in 1645, first used the term the Four Masters to describe the scholars who had compiled the Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland. He died in 1658 and one writer’s claim that “he restored her saints to the island of saints” has stood the test of time.

Hugh Ward 1593 – 1658

Hugh Ward was born into a Donegal family who were hereditary poets to the O’Donnells. He studied philosophy at the University of Salamanca in Spain, joined the Franciscans and in 1626 became the guardian of the Irish College in Leuven.

Hugh Ward was born into a Donegal family who were hereditary poets to the O’Donnells. He studied philosophy at the University of Salamanca in Spain, joined the Franciscans and in 1626 became the guardian of the Irish College in Leuven.

Ward was largely responsible for the establishment of the Leuven School of Hagiography which was dedicated to researching the lives of the Irish saints. At his instigation, friars and others were enlisted to transcribe hagiographical materials relating to Ireland in libraries all over Italy, France, Germany and the Low Countries. Soon, a substantial library of hagiographical material was assembled at Leuven.

The texts transcribed and collected on the continent were exclusively in Latin, so Ward made separate provision for Mícheál Ó Cléirigh to collect manuscript materials in Ireland, where they were vulnerable to the ravages of war or neglect. Ward’s work was to be one of the central pillars of what became known as the Grand Project. Ward himself died, probably of exhaustion, at the age of 42 leaving a huge collection of manuscripts.

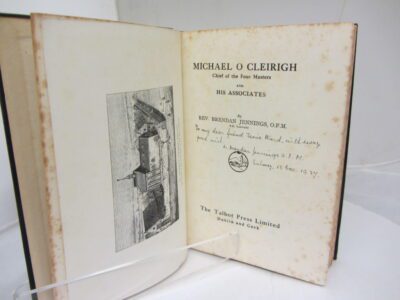

Mícheál Ó Cléirigh c. 1590 – 1643

Mícheál Ó Cléirigh was the most distinguished historian of the Franciscan project in Leuven. He was born Tadgh a’ tsléibhe Ó Cléirigh in Kilbarron, Co Donegal into the learned family of Uí Cléirigh who had practised bardic poetry and history in the Gaelic tradition throughout the late middle ages. Little is known of Ó Cléirigh until he became a lay brother in the Irish College in Leuven in 1623 and took the name Mícheál.

Mícheál Ó Cléirigh was the most distinguished historian of the Franciscan project in Leuven. He was born Tadgh a’ tsléibhe Ó Cléirigh in Kilbarron, Co Donegal into the learned family of Uí Cléirigh who had practised bardic poetry and history in the Gaelic tradition throughout the late middle ages. Little is known of Ó Cléirigh until he became a lay brother in the Irish College in Leuven in 1623 and took the name Mícheál.

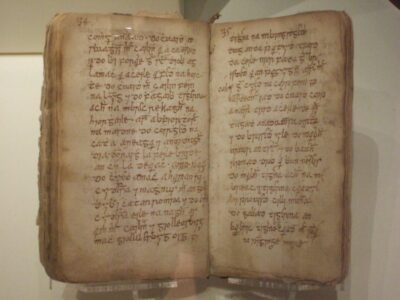

In 1626 Hugh Ward sent Ó Cléirigh to Ireland on a very special mission – to preserve and copy Ireland’s early literary manuscripts both civil and religious. From 1626 to 1637 Ó Cléirigh travelled the length and breadth of Ireland methodically collecting and copying manuscripts. To assist him in this work he brought together three other scholars Cú Choigríche Ó Cléirigh (Donegal), Cú Choigríche Ó Duibhgeannáin (Leitrim), and Fear Feasa Ó Maoil Chonaire (Roscommon). The result was the Annals of the Four Masters, the most celebrated work of the Irish College in Leuven.

Prior to commencing the annals, the same team prepared other new texts, the Genealogies of Saints and Kings and a new recension of Leabhar Gabhála or Book of Invasions.

This was an early account of the peopling of Ireland ending with the legend of Milesians. As well as showing ancient links to Spain, these works emphasised how in Ireland, as elsewhere in Europe, royal and saintly bloodlines intermingled.

After the Annals were completed, Mícheál Ó Cléirigh returned to the Irish College in Leuven, where he died in 1643 and was buried.

The Printing Project

From the outset, the Leuven friars were explicitly committed to intervening in their native country. In 1614 they took a decisive step. Supported by Archbishop Mattias Hovius of Mechelen they secured permission from Albert and Isabella to establish their own printing press because they “could not find in this country any printer who knows our language or characters”. By 1617, Donagh Mooney could report that his house “was exporting printed books of their own composition”. The printing project enabled the innovative activity in the field of Irish language, writing and historical scholarship through which the Irish College, Leuven would make its unique contribution to the Irish and the European mind.

From the outset, the Leuven friars were explicitly committed to intervening in their native country. In 1614 they took a decisive step. Supported by Archbishop Mattias Hovius of Mechelen they secured permission from Albert and Isabella to establish their own printing press because they “could not find in this country any printer who knows our language or characters”. By 1617, Donagh Mooney could report that his house “was exporting printed books of their own composition”. The printing project enabled the innovative activity in the field of Irish language, writing and historical scholarship through which the Irish College, Leuven would make its unique contribution to the Irish and the European mind.

The Leuven typeface was heavily influenced by the script style of manuscripts both in terms of letter-form and layout – tradition has it that the typeface is actually based on the handwriting of Bonaventure Ó hEodhasa, the Franciscan who instigated the printing project. The typeface was manufactured with the assistance of the famous Antwerp printing house of Plantien. This Leuven typeface set the standard for the reproduction of the Irish language for more than 350 years.

Early works published at the College included Florence Conry’s Desiderius and Hugh McCaughwell’s Scathan Shacramuinte na hAithride. Printing continued at the College until 1728.

The Four Masters were by no means the only historians in the 17th century engaged in the process of writing history using Irish manuscript sources. The Four Masters were influenced by the professional historian Lughaidh Ó Cléirigh, who wrote a biographical narrative of the Ulster leader Red Hugh O’Donnell. Another significant writer of Irish history was Geoffrey Keating who wrote Foras Feasa ar Eirinn in the 1630s. His work was extremely popular from its first appearance perhaps because – unlike the annals – it was written as a story, in a narrative prose.

James Ussher, the Church of Ireland Archbishop of Armagh, also used Irish manuscript sources – but to support a Protestant rather than a Catholic interpretation of Irish church history. Ussher claimed that the early church had been corrupted by Rome and that the Reformation was necessary to return it to its original purpose. He used Irish sources effectively to bolster his argument.

The Irish Colleges in Europe

Increasing English influence in Ireland during the early 17th century resulted in the escalation of the Protestant reformation and suppression of Catholic educational institutions. The establishment in 1592 of Trinity College, Dublin, nourished a Protestant intellectual elite whilst Catholic contemporaries looked to the continent for their education. Irish Colleges sprang up in strategic locations – countries where powerful sponsors were based, university towns where Irish academics and scholars were already located or where other ties existed.

Increasing English influence in Ireland during the early 17th century resulted in the escalation of the Protestant reformation and suppression of Catholic educational institutions. The establishment in 1592 of Trinity College, Dublin, nourished a Protestant intellectual elite whilst Catholic contemporaries looked to the continent for their education. Irish Colleges sprang up in strategic locations – countries where powerful sponsors were based, university towns where Irish academics and scholars were already located or where other ties existed.

The first Irish College was founded in 1592 at Salamanca, by 1611 there were twelve Irish colleges in Spain, France and the Low Countries. At its height, the network of colleges included more than 30 institutions and stretched from the Atlantic to the Baltic. This growing educational movement mirrored the increasing integration and influence of Irish migrants throughout the kingdoms and principalities of Europe. Yet, even as they concentrated on continental careers and occupations, many of the Irish abroad kept an eye on the island’s affairs and worked hard to influence what was happening there.

While some of the colleges were the responsibility of diocesan authorities, many were administered by religious orders, such as the Franciscans, Jesuits and Dominicans. Both clerical and lay students were educated in diverse subjects, with philosophy and theology being the most important. Each of the colleges had its own particular ethos- the College in Leuven was renowned for exceptional scholarship, networking, its significant political influence and its impact on Irish cultural identity. Within 40 years, the Irish Franciscans were deeply involved in three other continental colleges- in Paris, Rome and Prague.